Cecil Sharp – A Passion for the Revival of Folk Music in Uncertain Times

Posted on 16th November 2020 at 18:14

Here at the Music Workshop Company we love to share our knowledge about the history of music. We believe that learning about the rich cultural heritage of the country where we live provides a valuable, direct link to our local communities, and can be an interesting starting point for a journey of musical exploration.

As we hunker down to enjoy winter in the UK as the global pandemic forces ongoing travel restrictions, there seems no better time to meet one of the country’s greatest collectors and advocates of English folk music.

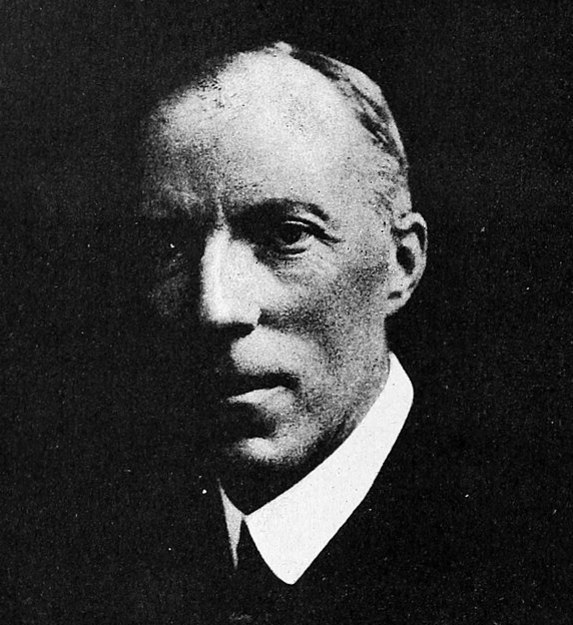

Cecil Sharp was born on November 22nd, 1859. Curiously, November 22nd is also Saint Cecilia’s Day the feast day of St. Cecilia who is known as the patron saint of music and musicians.

Sharp is known for his extensive collecting and archiving of English folk music and his collection is still kept at Cecil Sharp House in North London. However, very little is known about the man behind the collection, and his name can be divisive among folk-song scholars. One 2011 article in the Guardian describes why:

“The popular image is of a charming eccentric cycling around Somerset knocking on people's doors persuading old ladies to sing him their lovely old songs so he could save them from extinction, and preserve them through his books and lectures to provide a formidable harvest for future generations to enjoy and plunder. The conflicting modernist view is of a controlling manipulator who presented a false idyll of rural England by excluding anything that didn't fit his agenda, moulding himself as an untouchable icon of the folk-song movement in the process.”

Sharp’s schooling began in Brighton on the south east coast of England, but at the age of 10 he was sent to Uppingham, an independent school in the east midlands. While at school, Sharp became interested in music and theatre. He left Uppingham at 15, and was privately coached for Clare College Cambridge, where he went in 1879 to read mathematics.

On his father’s suggestion, having finished his university education, he travelled to Australia. There he worked for a while in various banking and legal jobs, while continuing his interest in music and teaching violin. In 1889 he resigned his job to begin a career as a full-time musician, as an organist, pianist, conductor and as a professor at Adelaide College of Music, where he was also joint director. During this time, he conducted the Adelaide Philharmonic and composed two light operas and an operetta.

Sharp returned to England in 1892. The following year, he married, and was appointed music master at Ludgrove School, a preparatory school for Eton College. From 1896, he was Principal at the Hampstead Conservatoire of Music.

In around 1903, Sharp began collecting folk songs. He became interested in English dance when he saw a group of Morris dancers and their concertina player at Headington, a village near Oxford at Christmas 1899.

“Sharp and his family spent that Christmas (1899) with his wife's mother, who was then living at Sandfield Cottage, Headington, about a mile east of Oxford. On Boxing Day, as he was looking out of the window, upon the snow-covered drive, a strange procession appeared: eight men dressed in white, decorated with ribbons, with pads of small latten-bells strapped to their shins, carrying coloured sticks and white handerkerchiefs; accompanying them was a concertina-player and a man dressed as a 'Fool'. Six of the men formed up in front of the house in two lines of three; the concertina player struck up an invigorating tune, the like of which Sharp had never heard before; the men jumped high into the air, then danced with springs and capers, waving and swinging the handkerchiefs which they held, one in each hand, while the bells marked the rhythm of the step. The dance was the now well-known morris dance, 'Laudnum Bunches', a title which decidedly belies its character. Then, dropping their handerchiefs and each taking a stick, they went through the ritual of Bean Setting. This was followed by 'Constant Billy' (Cease your Funning' of the Beggar's Opera), 'Blue-eyed Stranger', and 'Rigs o' Marlow'. Sharp watched and listened spellbound. He felt that a new world of beauty had been revealed to him. He had not been well; his eyes had been giving him pain, and he was still wearing a shade over them, but all his ills were forgotten in his excitement. He plied the men eagerly with questions. They apologised for being out at Christmas; they knew that Whitsun was the proper time, but work was slack and they thought there would be no harm in earning an honest penny. The concertina-player was Mr William Kimber, junior, a young man of twenty-seven, whose fame as a dancer has now spread all over England. Sharp noted the five tunes from him next day, and later on many more."

Cecil Sharp by A.H.Fox Strangeways, In collaboration with Maud Karpeles, Oxford University Press, London 1933.

This video shows footage of Cecil Sharp’s assistant, Maud Karpeles and her sister Helen performing some of the English dances in 1912. The Karpeles sisters formed the English Folk Dance and Song Society with Sharp.

During this period, Morris dancing was performed in regional forms in rural areas throughout England. The interest generated when Sharp notated the tunes meant the dances spread to urban areas too.

At the same time, music teaching during this period was based on methods that originated in Germany. Because of this, music learning focused on German folk tunes. As a music teacher, Sharp became curious about the vocal and instrumental (dance) music of the British Isles, in particular the tunes. He believed that it was important for people to become aware of the heritage of melodic expression that had developed in the different regions.

Sharp was attracted to folk music by the experience at Headington. Initially he sought out folk songs collected in existing publications, such as Chappell’s Popular Music of the Olden Time. However, he soon realised that there was a marked difference between the versions of tunes he was finding in these books and transcriptions of more recent collectors like Lucy Broadwood, English folksong collector and researcher, and great-grand-daughter of John Broadwood, founder of the piano manufacturers Broadwood and Sons.

Sharp partnered with Charles Marson to produce the three-volume work, Folk-Songs from Somerset. This collection stretched to more than 1,600 tunes and texts, collected from 350 singers. Sharp used these songs in his lectures, and in a press campaign to promote the rescue of English folk song. Although he subsequently collected songs from 15 other countries, the Somerset songs were at the heart of his work.

Before the Great War, Sharp walked and cycled many miles, collecting songs, tunes and dances. Between 1911 and 1913 he published another three-volume work, The Sword Dances of Northern England, which described the obscure and nearly extinct Rapper sword dance of Northumbria and the Yorkshire Long Sword dance. This led to the revival of both traditions in their home areas and further afield.

Part 5 of the Morris Book was published in association with the English composer, George Butterworth, in 1914. Butterworth was shot through the head by a sniper in 1916 during the battle of the Somme. His body was never recovered.

Or as the Guardian article rather snidely describes it:

“At a time when other folk song collectors such as George Butterworth were dying in the trenches during the first world war, Sharp was on a mission in the US, battling ill-health exacerbated by the oppressive climate as he obsessively attempted to unravel the heart of the old world in the purity of folk songs he found in the new. "It is strenuous work," he wrote. "There are no roads in our sense of the word ... I go about in a blue shirt, a pair of flannel trousers with a belt, a Panama hat and an umbrella. The heat is very trying ..."”

Sharp’s diaries are described as informative, but according to the English folk singer, Jim Moray, speaking in the Guardian, “they just say things like '2pm: dinner with Miss Hamer. 6pm: theatre.' If he had ulterior motives – whether political or whatever – they weren't mentioned or documented.” Moray goes on: “Most people have arrived at this idea of him being a controlling, sanitising man, but… I just think he was very driven.”

Cecil Sharp died on Midsummer's Eve, June 23rd, 1924. He left a huge and immensely valuable body of work and was, in some ways, single-handedly responsible for the revival of knowledge and interest in regional and national folk music in the British Isles. He left very little information about who he was as a person, or what really drove his great passion. But perhaps anyone with an interest in folk music will understand. These songs and dances make up an important part of England’s history. They connect people with their ancestors and with an older way of life. They cement communities together, provide entertainment and enjoyment. And, when all’s said and done, there’s always another great tune waiting to be played.

Here at the Music Workshop Company, we thrive on introducing participants to an enjoyment and understanding of music. However, all our workshops have a deeper purpose and significance too. We explore music from different cultures, and engage with curriculum topics, facilitating team building work, communication skills and experiential learning which build confidence and facilitate creativity.

If you found this blog interesting and useful, you may enjoy reading our blog about English folk music.

Click here to listen to Cecil Sharp’s daughter Joan playing English folk tunes.

Click here to read the article in the Guardian.

Share this post: