Irish Song – A Window on History

Posted on 15th February 2017 at 14:30

Irish traditional music has existed for centuries, with songs and dance tunes passed on from generation to generation through the oral tradition. This practice of learning ‘by ear’ is still common today. Despite the number of printed tune and songbooks, students of traditional music generally learn tunes by listening to other musicians.

The traditional music that developed in Ireland first arrived with the Celts. Until the last decade or so, scholars dated the ‘arrival’ of Celtic culture in Britain and Ireland to the 6th century BC. However, recent research has given rise to the idea that Celtic culture emerged in Britain and Ireland much earlier – in the Bronze Age – suggesting its spread was the result not of invasion, as previously thought, but of a gradual migration enabled by an extensive network of contacts that existed between the peoples of Britain and Ireland and those of the Atlantic seaboard.

The Celts were originally from Europe – countries including Austria, evidenced by rich burial-site finds, Northern Italy, and even as far east as Turkey. By the middle of the 1st millennium AD, with the expansion of the Roman Empire and extensive migrations of Germanic peoples, Celtic culture had become restricted to Ireland, the western and northern parts of Great Britain (Wales, Scotland, and Cornwall), the Isle of Man, and Brittany. Between the 5th and 8th centuries, the Celtic-speaking communities in these Atlantic regions emerged as a reasonably cohesive cultural entity, with a common linguistic, religious and artistic heritage that clearly distinguished them.

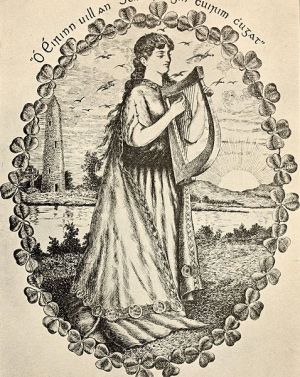

The Celts were influenced by music of the East. It is believed that the traditional Irish harp may in fact have its roots in Egypt. In ancient times the harp was one of the most popular instruments. Harpists were employed to play for chieftains and to create music for noblemen. In 1607, native Irish chieftains fled under threat of invasion, leaving the harpists to travel the land as itinerant musicians, playing where they could. One of the most famous of these harpists was Turlough O’Carolan, a blind musician and songwriter born in 1670 who travelled throughout his life from one end of Ireland to the other, composing and performing.

There are several collections of Irish folk music from the 18th century, and by the 19th century ballad printers were established in Dublin.

Like all traditional music, Irish folk music has evolved slowly, and most of the folk songs around today are less than two hundred years old. Where the oldest songs and tunes are from rural settings and come from the Celtic language tradition, the more recent songs generally come from cities and towns and are written in English.

The ultimate expression of traditional singing is an old-style called sean nós. This is usually performed solo, or very occasionally as a duet. Sean-nós singing is highly ornamented, with the voice placed towards the top of the range. A true old-style singer will vary the melody of every verse, but not to the point of interfering with the words, which are considered to have as much importance as the melody.

Non sean-nós traditional singing, even when accompanied, uses patterns of ornamentation and melodic freedom derived from sean-nós singing. It also uses a similar voice placement. This song from the Irish band Altan shows a more modern take on the traditional style.

Caoineadh is Irish for a lament. There are many laments in the Irish song repertoire, expressing sorrow and pain, often of a person lamenting for Ireland itself, having been forced to emigrate due to political or financial reasons. Laments were also used to express loss of a loved one or have their roots in war or the various economic crises caused by both partition and war. This song, Far Away in Australia, is a lament as an Irishman leaves home to seek better fortune, but like many Irish ballads is imbued with hope for the future.

The song, Mo Ghile Mear, written by Seán Clárach Mac Domhnaill, is a lament of the Gaelic goddess Éire for Bonnie Prince Charlie, who was in exile.

The Wind That Shakes the Barley relates to the Irish Rebellion of 1778. Written by Robert Dwyer Joyce (1836-1883), it expresses a young man’s sadness at leaving his lover to join the United Irishmen, a sorrow that is cut short when she is killed by an English bullet.

Other aspects of Ireland’s history are found in popular songs such as Whiskey in the Jar, which tells of the betrayal of highwayman Patrick Flemmen who was executed in 1650. This ballad became a signature song for The Dubliners in the 1960s and was even recorded by Thin Lizzy and Metallica.

Share this post: