The Influence of African Musicians on Classical Music

Posted on 18th September 2017 at 14:00

Western classical music, by its very definition, is rooted in the sacred and secular traditions of the western world, centred around Europe. Although the genre has been influenced throughout history by folk song, jazz and music from other continents such as America and China, it rarely diverges far from its Western identity.

Much like Western music outside the ‘classical’ box, African music is incredibly diverse, varying greatly by region. There is lots of opportunity for creative inspiration.

In his 2006 book, Listening to Artifacts: Music Culture in Ancient Israel/Palestine, Theodore Burgh suggests that classical music ultimately has its roots in North Africa, in the art music of Ancient Egypt, as well as other ancient cultures such as Greece. However, there seems, at first glance, little evidence of African influence in classical music. When it is found, for example in Tippett’s A Child of Our Time, it is generally Afro-American in origin, interpreted in a western-dominated form of music.

When explored, the contribution of black composers and musicians, and the influence of African music, forms a fascinating part of classical music history.

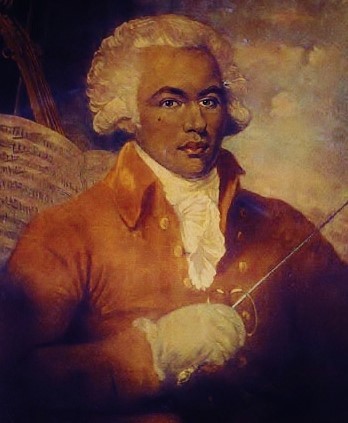

Joseph Bologne, Chevalier de Saint-Georges

Probably the first and perhaps best-known classical composer of African descent, Saint-Georges was the illegitimate son of a Guadeloupe plantation owner, Bologne de Saint-Georges, and his mistress, an African slave girl of probable Senegalese birth called Nanon.

A contemporary of Mozart, Saint-Georges was barred from sharing his father’s French noble status because he was black, but his father ensured he was educated as an aristocrat. He studied fencing with a famous swordsman, becoming a champion fencer. He learned harpsichord, and he studied violin with one of the famous French virtuosi, Jean-Marie Leclair the Elder. His success both as a musician and athlete made him famous, but while religious leaders were agitating for an end to slavery, interracial marriages were still forbidden, and his skin colour built him an ambivalent status in society.

Although close to Queen Marie Antoinette, Saint-Georges was refused the prestigious post of director of the Paris Opéra, for which he was considered in 1775, because two of the company’s leading sopranos objected and successfully petitioned the Queen against his appointment on the ground of his race. Even so, he was a major star in Paris in the 1770s, nicknamed “Le Mozart Noir” on concert posters, often sharing equal billing with Mozart.The later part of Saint-Georges’ life was disrupted by the French Revolution. Although he had been active in campaigning against slavery and sympathised with the democratic aims of the revolution, his aristocratic background meant he was not trusted.

He continued performing and directing up to his death, and he was remained famous enough to attract large crowds. However, living alone, he contracted a bladder infection and died on June 10, 1799.

Commemorative editions of his music were published, but within a short time, new restrictions on blacks came into force across France and its empire. Slavery had been abolished in 1794, but was re-imposed by Napoleon Bonaparte. Under Bonaparte’s regime, Saint-George and his music were removed from orchestra repertoires, wiping him from the history books for nearly 200 years.

His profile has risen in recent years thanks to concerts by ensembles including the Orchestra Of The Age Of Enlightenment, but he has not yet regained the equal footing he held with Mozart among classical music fans.

Embracing Ideas in the Romantic Period and Beyond

Towards the end of the 19th century, composers were looking towards different cultures for inspiration. Antonín Dvořák’s interest in themes from the ‘new world’ is well documented. His move to New York brought him directly into contact with Afro-American music.

In fact, Dvořák’s Ninth Symphony, From the New World, written in 1893, contains some of the most famous examples of Afro-American themes in classical music. But Dvořák’s themes are not actually of Afro-American origin. The composer wrote accurate imitations of the pentatonic melodies, a technique which he also used in his American string quartet.

Interestingly, these compositions were pretty much contemporaneous with an emerging style of music in North America called ragtime.

Ragtime descended from the jigs and marching music played by African American bands, referred to as “jig piano” or “piano thumping”. Rags by Scott Joplin such as The Entertainer and Maple Leaf Rag are still instantly recognisable, and Ragtime had a lasting influence on classical composers. Igor Stravinsky wrote a solo piano work called Piano-Rag-Music, while ragtime is evident in the works of Erik Satie, Arthur Honegger, Darius Milhaud and the other members of The Group of Six in Paris.

In 1930, William Grant Still’s Afro-American Symphony marked the first symphony by an African-American man. The work marries conventional classical forms with popular African styles, also referencing the blues. The bass line of the final movement moves from an F to a D-flat, resembling Dvořák’s New World Symphony.

The following epigraph, from African-American poet Paul Laurence Dunbar’s 1896 work, Ode to Ethiopia, appears with the fourth movement:

Be proud, my Race, in mind and soul,

Thy name is writ on Glory’s scroll

In characters of fire.

High ‘mid the clouds of Fame’s bright sky,

Thy banner’s blazoned folds now fly,

And truth shall lift them higher.

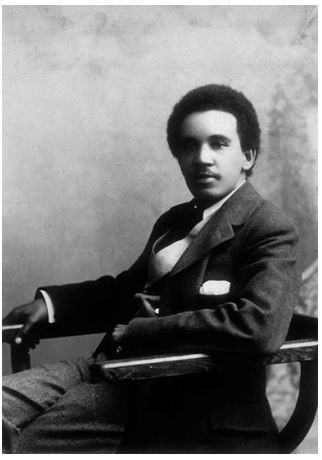

Samuel Coleridge-Taylor

The composer Samuel Coleridge-Taylor (1875-1912) is considered to be the only black composer to have broken through from the Romantic era. Born to a Sierra Leonean father, Coleridge-Taylor was from Holborn, London. He incorporated black traditional music with classical music, with such compositions as African Suite, African Romances and Twenty Four Negro Melodies. The first performance of his work, Hiawatha’s Wedding Feast, was described by the principal of the Royal College of Music as, “One of the most remarkable events in modern English musical history.” Despite this success, Coleridge-Taylor’s music is out of fashion and all-but out of print.

Accepted to the Royal College of Music aged 15, despite concerns about his skin colour, he swapped violin studies for composition. His tutor was Charles Villiers Stanford. Stanford challenged his student to write a clarinet quintet without showing the influence of his favourite composer, Brahms. Coleridge-Taylor wrote the piece, and when this work was revived in 1973, the New York Times critic called it, “Something of an eye opener…an assured piece of writing in the post-Romantic tradition…sweetly melodic.”

Despite little modern recognition, his influence lives on: From 1903 to his death in 1912, he was professor of composition at the Trinity College of Music in London. However, violinist Philippe Graffin performed the violin concerto at the Proms in 2005, and the Nash Ensemble have recorded the composer’s piano quintet.

Modern Times

Modern classical music has been more influenced by African culture. John Cage’s 1940 work, Bacchanale was the first significant modern synthesis of African and Western music. It was also instrumental in the development of the prepared piano, as the composer sought out African sounds with only room on stage for a grand piano.

Other composers such as George Crumb, Ligeti and Steve Reich have explored African influences, while composers born in Africa include Nigerian composer Joshua Uzoigwe. A member of the Igbo ethnic group, many of Uzoigwe’s works draw on the traditional music of his people.

Classical music is far from reaching the limits of inspiration from African music, and it is far from incorporating the work of black composers on a level playing field. However, for centuries, composers and the curiosity of the creative mind have shown us that the more the classical music world stretches its knowledge beyond the boundaries of its own traditional culture, the more unique voices will be found.

Tagged as: AFRICAN COMPOSERS, BLACK COMPOSERS, CLASSICAL MUSIC, JOSEPH BOLOGNE, SAMUEL COLERIDGE-TAYLOR, SCOTT JOPLIN

Share this post: