Celebrating pantomime: an art form where the audience is king

Posted on 15th December 2022 at 10:06

It’s panto season! (Oh no it isn’t…)

Okay, we’re sorry. Terrible jokes aside, this December we take a look at one of the quintessential British traditions of the festive season: the Christmas pantomime. It’s a format that has endured for many years, and one that puts the audience at its centre. For decades, the panto has provided an important first experience of live performing arts for many young children in the UK. But where did it come from, and how has it survived?

Image: Two pantomime dames at Arts Fest (credit: roogi)

The word ‘pantomime’ comes from the Latin ‘pantomimus’, which was used in ancient Rome to describe a dancer who acted all the parts in a tale, using masks, gestures and mime to distinguish between characters. The story would often be based on Greek mythology, and the performance would be accompanied by music, usually from a flute or chorus.

From the commedia dell’arte to Harlequinades

But in fact, the roots of modern pantomime are in the 16th century, in an Italian street theatre tradition known as commedia dell’arte. The theatrical form was toured around Europe, popping up in markets and fairgrounds where its cast of masked characters proved popular with local crowds. And while these street comedies would have looked very different to the tradition of panto that we know and love today, they contained many elements that modern audiences would recognise: a well-trodden story featuring stock characters in exaggerated costumes, the triumph of good over evil, plenty of physical comedy and topical jokes, and – crucially – a reliance on music.

A typical commedia production included several well-known characters such as the old man Pantalone, his mischievous servant Pulcinella, the sad clown Pierrot, the acrobatic servant Arlecchino and his love interest, Colombina. In 17th and 18th century England, Arlecchino became Harlequin, the hero of the story – a clever comedian whose spirits were always high. Harlequin’s wooden stick, which he used to hit the scenery and trigger changes in the set, gave rise to the word ‘slapstick’.

Perhaps because they sometimes used classical mythology as the basis for their stories, and relied on music and dance – much like those ancient Roman performers – the word ‘pantomime’ became attached to these ‘Harlequinade’ productions.

The rise of modern panto

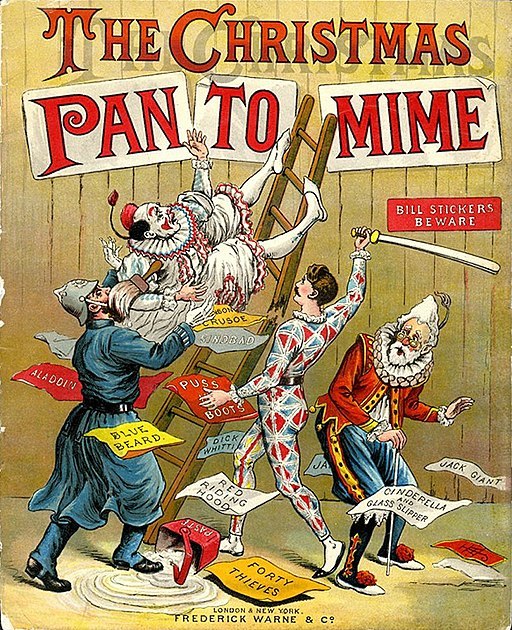

The cover of an 1890 book, The Christmas Pantomime, showing Harlequinade characters

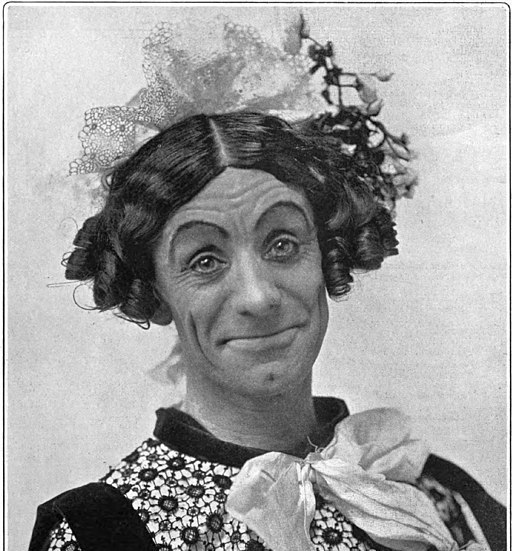

It was a music hall comedian, Dan Leno, who cemented the panto dame in the early 20th century as a must-have character in every festive production.

Katie Shilton, of pantomime producers Imagine Theatres, writes:

“As characters in the commedia wore masks that were instantly recognisable to audiences who were familiar with that character, the elaborately painted face of a pantomime dame acts almost as a mask in the same way…we immediately know what character we are looking at.”

Image: Dan Leno, the first ever pantomime dame

Eventually, though, these classical stories began to fall out of favour, and scriptwriters turned instead to folk and fairy tales for inspiration. Stories like Cinderella, Sleeping Beauty, Little Red Riding Hood and Puss in Boots started to make an appearance – titles that wouldn’t be out of place in a pantomime today.

By the early 1800s, sets were becoming more lavish and elaborate, with theatres vying to outdo each other’s productions. With the help of the actor Joseph Grimaldi, the character of the Clown became much more important – and some of his later performances, for example as Baroness in Harlequin and Cinderella, paved the way for the panto dame.

As Victorian era music halls became popular, theatres began to fill their lead roles with the best-known music hall entertainers of the day. The tactic guaranteed ticket sales, and has been continued ever since with stars of radio sought after during the 1930s, and famous faces from TV cast in today’s pantomimes.

Music and tradition

Pantomimes are often viewed as a British tradition that doesn’t change. In truth, it’s an art form that has always adapted with the times. But there are some things that most modern audiences would view as absolute rules for a panto, including:

The panto dame. Played by a male actor in women’s clothing, the dame is a comic figure, but one who often wins the audience’s sympathy. And she’s not the only cross-dressing character in pantomime history – in Victorian times, the Principal Boy was usually played by a woman, a tradition that lasted for decades and had a brief resurgence in the 1980s and 90s. In this way, panto lets audiences know very clearly that it has no qualms with subverting their expectations.

Good battling evil (and winning). A panto is a feel-good, family show, and it must have a tight plot with the heroes defeating the evil villain – or even better, winning them over to the good side. In many pantomimes, the villain enters first from stage left, followed by the good fairy from stage right. This tradition can be traced back to medieval times when these sides of the stage represented heaven and hell.

Slapstick comedy. Harlequin’s set-changing ‘slapstick’ is a thing of the past, but the sort of physical comedy that is guaranteed to have young audiences howling with laughter remains a firm fixture. The messier the comedy is, the better: a ‘slosh’ scene filled with custard pies in the face always goes down well.

Music – and lots of it. Music is incredibly important to pantomime, just as it was in those early street performances in the 1500s. A good score will signal to audiences how to respond to different characters and plot twists: every pantomime villain needs some dramatic music to announce their entrance. Characters will express themselves through songs, often set to a familiar tune of the day with the lyrics re-written to suit the story. And of course, some of those songs rely on the audience getting involved too, which leads us to our most important tradition…

Audience participation is key

No panto is complete without its audience! Few theatrical productions ‘break the fourth wall’ as much as pantomime does. The open invitation to take part and interact with the performers is one of the great joys for younger audience members. The highlight of any panto, often just before the finale, is the ‘song sheet’, where children are selected to join the cast on stage. Lyrics are displayed for all the audience to sing along, often with a competition to see which half can sing the loudest.

For many children, the Christmas pantomime will be their first experience of live theatre and music. Being encouraged to sing, boo, hiss and cheer, and to shout ‘Oh no it isn’t! or ‘It’s behind you!’ is a rite of passage – and it may just be the seed that sparks a lifelong interest in the arts. So, while pantomime may continue to adapt and develop new traditions, we can only hope that audience participation is a tradition that will stay for good.

Further reading:

The V&A Museum on the story of pantomime: https://www.vam.ac.uk/articles/the-story-of-pantomime

The BBC’s Michael Grade explores the origins of panto: https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/articles/2JZ6TSqnd480n90dzN77r1Q/where-does-pantomime-really-come-from

Imagine Theatres’ take on pantomime’s history: https://www.imaginetheatre.co.uk/history-of-pantomime

Alex Jackson Pantomimes on the must-have traditions of panto: https://www.alexjacksonpantomimes.com/a-beginners-guide-to-british-pantomime-traditions/

Share this post: