Mixed Messages for Music?

Posted on 29th May 2019 at 14:30

The Sound of the Next Generation is a new research report by Youth Music and Ipsos MORI. It gives insights into the wide range of ways in which young people engage with and value music and music making. But does it offer any new answers? MWC’s Maria Thomas finds out more…

Youth Music’s research was carried out in 2018 by means of online surveys. 1,001 young people aged between 7 and 17 from across England participated. The results were analysed by industry leaders, psychologists and academics in order to evaluate the findings in the wider context of music in society.

The release of the ensuing report has sparked online debate. For example, a call to widen the genres of music covered in schools was seen by some as a suggestion that classical music should be cut from the curriculum. Youth Music took to Twitter to respond:

Despite the headlines Youth Music are not suggesting Stormzy instead of Mozart, we are suggesting Stormzy AND Mozart and many things in between!

The report covers several key themes:

How integral music is to young peoples’ lives

How much music young people are making

The patterns of engagement with music

The impact on wellbeing

The diverse pool of talent potentially making its way into the music industry

Whatever the state of music in schools, it returns a somewhat positive picture when it comes to engagement. 97% of young people surveyed had listened to music in the last week. 69% of young people had watched a music video in the last week, (80% of 16-24 year olds watch YouTube, averaging 487 videos a month!), and 32% of 16 – 17 year olds listed class music as their favourite activity. Music is still very relevant.

Singing has particularly strong participation. 71% of 7 – 10 year old girls sing regularly, and 85% of young singers say singing makes them happy. Musical confidence is improving, with 64% of young people saying they think they are musical, up from 48% in 2006. But while 30% of young people play a musical instrument there’s a question around specialist teaching. 23% are taught by a friend or family member and 25% are teaching themselves.

The Findings

Music is integral to young people’s lives

In England, the primary pastimes of young people are music and gaming. A massive 97% of respondents had interacted with music in the week leading up to the research. Most young people listen to music on a mobile device such as a smartphone or tablet, on their own, and 76% said they mostly listened to music whilst doing something else.

Perhaps surprisingly with the growth of streaming and the popularity of YouTube, 64% of respondents listened to the radio each week. But attendance at live gigs is low. Only 11% of respondents had seen music played live in the week leading up to the research.

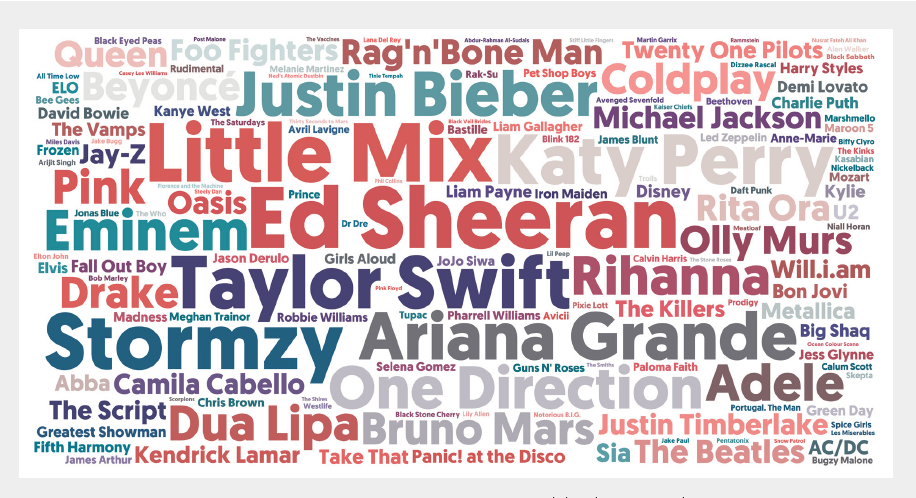

The easy access to music through streaming has prompted young people listen to a wide range of genres with participants naming 633 different artists spanning more than 300 different kinds of music.

Young people are making more music than they were a decade ago

Two thirds of young people reported engaging in some form of music-making activity: Most commonly singing and playing an instrument, followed by karaoke and making music on a computer. The sheer amount of music making has increased significantly since 2006, when a similar survey conducted by Youth Music found that just 39% of young people made music on a regular basis. This increase is perhaps due to advances in digital technology and the freedom that gives for young people to make music independently.

The number of young people who play an instrument has also increased since the previous study, rising to 30% from 23% in 2006. The availability of study resources such as ‘teach-yourself’ YouTube videos has made this increase possible, along with a Government policy that aims to ensure all children of primary school age get the chance to play an instrument.

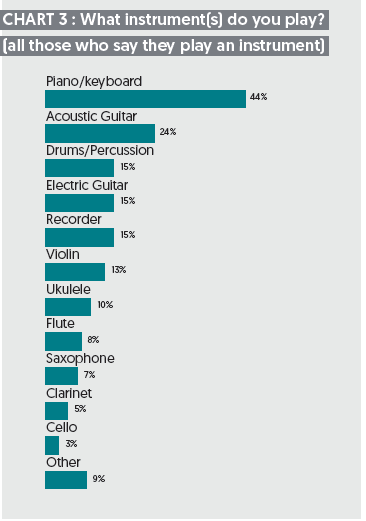

However, the range of instruments chosen is limited:

Youth Music’s report reinforces the findings of other studies, showing that participation in music-making drops significantly as children get older. A third of all 7-10-year-olds say they play an instrument, but only one in four is still playing at the ages of 16-17. There’s also a big gender gap with boys much more likely to stop playing. Participation in after-school music clubs peaks among 11-15-year-olds, where 43% participate, but this nearly halves by sixth form age.

As discussed in previous MWC blogs, GCSE and A Level Music exam entry rates are currently falling annually. Research puts blame on the introduction of the Ebacc and the negative effect of the music curriculum offering in state secondary schools. This new report echoes that concern:

Shrinking of school-based music opportunities is significant. Music teachers and music rooms are an essential part of school life – providing space and advice for young people to form their own bands, develop lasting friendships, take part in school musicals and after-school activities, and access instruments and rehearsal rooms to practice their craft.

Patterns of engagement differ according to a young person’s background

The Sound of the Next Generation report highlights that those from lower income backgrounds have very different patterns of engagement with music than those from higher income backgrounds.

While many young people with limited financial means are experiencing a rich musical childhood, their experience is quite different to that of their more affluent peers:

"It’s more likely to emanate from their home, have a DIY feel to it and less likely to be taught in a formal way. Often it’s ‘everyday creativity’ – activity which is already happening in people’s lives, an accessible form of culture that they can engage in."

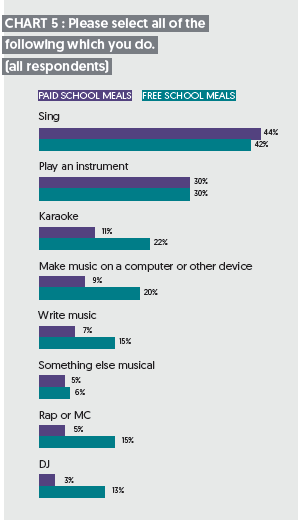

Notably, 76% of those in receipt of free school meals describe themselves as musical. This is significantly higher than the 60% of students who don’t receive free meals. Students receiving free meals were just as likely as other young people to sing and play an instrument but were much less likely to have seen music at a concert or gig (50% vs 27%). Conversely, they were twice as likely to have seen live music played at home in the last week (45% vs 21%) and also more likely to be involved in certain types of musical activity such as karaoke, making music on a computer, writing music, DJing and rapping.

The wider evidence base shows that from age 11 onwards, economic background is a major barrier to participation in certain types of music education. A 2014 ABRSM report found that 74% of young people from the 20% wealthiest backgrounds had received instrumental lessons and were twice as likely to have taken a music exam as those in the lowest 25% income bracket. At the other end of the spectrum, just 6% of regular participants in Music Education Hub ensembles and choirs are eligible for the ‘pupil premium’ (additional funding given to schools to support young people experiencing economic or family difficulties).

Within this challenging environment, Youth music’s report points to a rise in the number of ‘bedroom musicians’. Almost one in five young men say they make music on a computer. Access to online resources allows young people to learn independently and to compose using open source software, potentially leading to the beginnings of a musical career.

The report highlights the importance of offering advice on legal issues and other risks in the music industry, explaining:

"Bedroom musicianship and karaoke-style apps are part of a suite of activities that develop young people’s musical identity but often go unrecognised in formal music education. This is a missed opportunity to engage young people and support them in their musical development."

Music is a powerful contributor to young people’s wellbeing

Another topic we’ve covered before in the MWC blog is the wellbeing of young people, and in particular their mental health. In 2016, The Association of School and College Leaders and National Children’s Bureau identified that over five years, 90% of school leaders reported an increase in the number of students experiencing anxiety or stress and low mood and depression. The Office for National Statistics highlighted in 2017 that an estimated three children in every 20 have a diagnosable mental health problem.

Youth Music’s report found that 85% of young people said that music made them feel happy. Large numbers also said it made them feel cool (41%) and excited (39%). Wider qualitative research has suggested that young people choose different genres of music for different moods, but that they often like to be ‘mood-congruent,’ i.e. to listen to music that reflects how they’re feeling.

Research suggests that the creative process of making music has a deeper and more profound impact than listening to it. This was backed up by recent findings that young people see music making as a vital part of their lives and something that makes them feel worthwhile.

A diverse talent pool of young people supports the future of the music industry

The findings identify that a gap exists between music education and the music industry, suggesting that young people often aren’t aware of the opportunities available in the industry or the paths they need to follow to pursue a musical career. Widening access to pathways into industry for artists and those behind the scenes is vital to the future of the music industry.

The report also suggests that due to systemic biases, and the concentration of music industry jobs in London, the demographics of those currently working in the music and the wider creative industries are not representative of the population as a whole. This is further challenged by the ongoing practice of unpaid internships as a pathway to entry-level employment. While many large organisations do offer paid internships, 86%of internships across the Arts were unpaid.

It recommends that:

"Music education in schools must be maintained but should be re-imagined, with a new model – supported and valued by Ofsted – that’s more aligned with young people’s existing musical identities and with outcomes that go beyond attainment to better capitalise on music’s social value. Music education should be more industry-facing in its curricula and partnerships and better consider the needs of DIY musicians. Digital technologies should be embedded, and programmes should prepare young people for a wide variety of industry roles including what’s required to have a successful freelance career."

The report concludes with a call for greater collaboration between the industry and educators, stating that routes into the industry are changing. However, the concerns about a lack of acknowledgement of classical music may be valid, as the report seems predominantly relevant to the commercial music sector.

It leaves open two questions:

How can we ensure that young people are exposed to a wide range of musical opportunities both in terms of listening and learning?

And how can young people be supported to pursue the musical opportunities that are right for them?

You can read the full report here: https://www.youthmusic.org.uk/sound-of-the-next-generation

Tagged as: MUSIC AND YOUNG PEOPLE, MUSIC EDUCATION

Share this post: