The great improviser: celebrating 200 years of César Franck

Posted on 16th November 2022 at 12:25

This year marks the double centenary of César Franck, the French composer known for his romantic style and his skill in improvisation. But for much of his life, Franck’s compositions at best split opinion, or worse, failed to win critical praise or even much public attention.

To mark the 200th anniversary of his birth, we take a look at his musical career and ask: how did he finally make his mark, and why has he endured for so long after spending so many years in relative obscurity?

Franck’s musical style

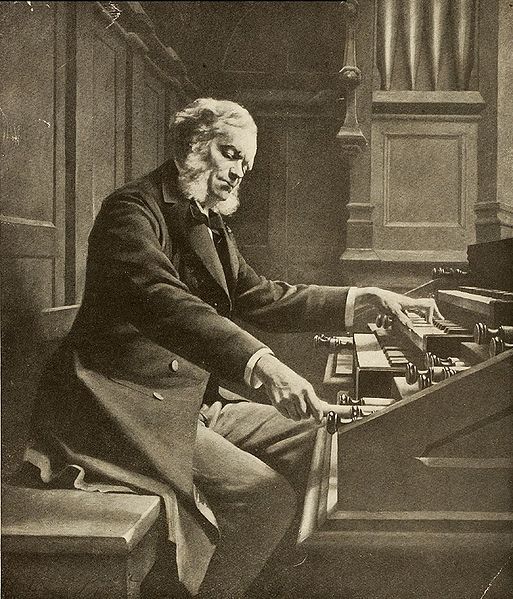

Franck was born in 1822 in Liège just a few years before it became part of newly independent Belgium, but he spent much of his life in France. His music fits squarely into the tradition of French Romanticism, an expressive, lyrical style that worked to convey moods and emotions. Many of Franck’s works took a cyclic form, repeating motifs that were used to create unity and a theme across separate movements. He was also a master of improvisation, and people used to come from afar to hear him play organ at the Basilica of St Clotilde, where he worked for many years.

His best-known piece, Panis Angelicus, has been performed and recorded the world over, with its simple melody for a tenor voice often set against strings or a muted organ accompaniment. But it wasn’t completed until relatively late in his career, and this is true of many of Franck’s compositions that are still regularly played today.

Even then, many of the works that he is so admired for today were not universally loved when they premiered. Still, in the last 20 or so of years his life, he found much more success compared to his early years, when he struggled to gain critical acclaim.

Early music education

Franck showed an early talent for music that was quickly recognised by his father, who enrolled him in the Royal Conservatory of Liège before moving him to France to study at the Paris Conservatoire, along with his brother. Franck excelled there, winning first prize for piano in his first year and going on to take further prizes in counterpoint and organ.

Unfortunately for Franck, however, his father’s ambitions were more focused on bringing the family fame and fortune than they were on allowing his sons to pursue their passions. The young musician, who had hoped to compete for the prestigious Prix de Rome, was instead forced to leave the Conservatoire in order to take up a gruelling new schedule: touring as a concert pianist, and teaching on the side to generate more income.

With his father driving him hard, it is perhaps not surprising that his compositions at this time often failed to hit the mark for many critics. It’s been suggested that many of the pieces he wrote for his concert performances were too ‘showy’ to sit well with Franck’s humble character – although works like Souvenirs of Aix-la-Chapelle, written in 1843, give early hints of what was to come in his later years. But it was not until he was able to break away from his father’s grip that he would find the freedom to explore his own creative path.

Obscurity – and a return to public life

That break came in 1848 when he married one of his students, Félicité Desmousseaux, against his father’s wishes. It was at this point that Franck stopped using the full name ‘César-Auguste’ that his parents had given him, calling himself simply César instead. He all but retired from public life, becoming a church organist and teacher.

But this move into semi-obscurity was, in fact, the start of a journey that would see him develop the improvisational style for which he would later become renowned. When he moved to a new church in 1851, he was able to try out a new organ made by the famous Aristide Cavaillé-Coll, and he described it as being ‘like an orchestra’.

The sound he was able to produce from this instrument caught its maker’s attention, and Franck soon began to work with Cavaillé-Coll, travelling the country to demonstrate his new organs – all the while gaining a reputation as an excellent improviser. It’s said that his large hand-span contributed to his considerable keyboard skills, with some of his pieces being notoriously difficult for others to play!

In 1858, he took up a position as organist at the Basilica of St Clotilde in Paris, where he would remain for the rest of his life, even after his star began to rise again. Here, he began to give recitals of his own compositions, and caught the attention of the composer Franz Liszt, who worked to bring Franck’s music to a wider audience.

It wasn’t until 1872 that he returned to the Paris Conservatoire as a professor, taking French nationality to do so. It was during this period that he composed some of his most successful and enduring works – such as his Violin Sonata and the Symphony in D minor. Many of his latter-day compositions have since become standards in classical music: here at The Music Workshop Company, the Symphony is a particular favourite of our Artistic Director, Maria Thomas, for its use of the cor anglais.

Franck’s approach to music teaching

As a teacher at the Paris Conservatoire, Franck gained a new reputation among his students, who referred to him as ‘Père Franck’ and became his loyal followers. Those students included many young musicians who would go on to be famous composers in their own right – including Vincent D’Indy, Paul Dukas, Henri Duparc and Louis Vierne – and together they worked to draw public attention to their teacher’s output, organising concerts of his works (often with varying success).

Franck, though, was not hungry for fame, however much his father would have liked him to be. He was an unassuming, humble and industrious man, and in his approach to music education, his biographer Timothy Flynn describes Franck as “a compassionate, patient, and exemplary teacher. The success and welfare of his students was always at the forefront of his thoughts.” It’s clear that Franck was creating a very different sort of learning environment for his pupils compared to the one he himself had experienced all those years before.

We will never know what else he might have produced had his life not been cut tragically short in 1890. The impact he had made is clear from the huge number of notable composers and musicians who attended his funeral, including Léo Delibes, Camille Saint-Saëns, Eugène Gigout, Gabriel Fauré, Alexandre Gilmant, Édouard Lalo, Emmanuel Chabrier – who spoke at his gravesite – and Charles-Marie Widor, who would take on Franck’s former role as professor of organ at the Conservatoire.

The works he contributed still resonate today, and in passing down his ideas about music to his students, Franck had a far greater influence on musical history than he could ever have hoped for.

Further reading

ClassicalNet’s biography of Franck is available at: http://www.classical.net/music/comp.lst/franck.php

Classic FM’s take on the composer can be found at: https://www.classicfm.com/composers/cesar-franck/

G Henle publishers explore Franck’s life and music in this post: https://www.henle.de/blog/en/2022/05/23/between-two-stools-a-portrait-of-cesar-franck-on-his-200th-birthday/

Share this post: