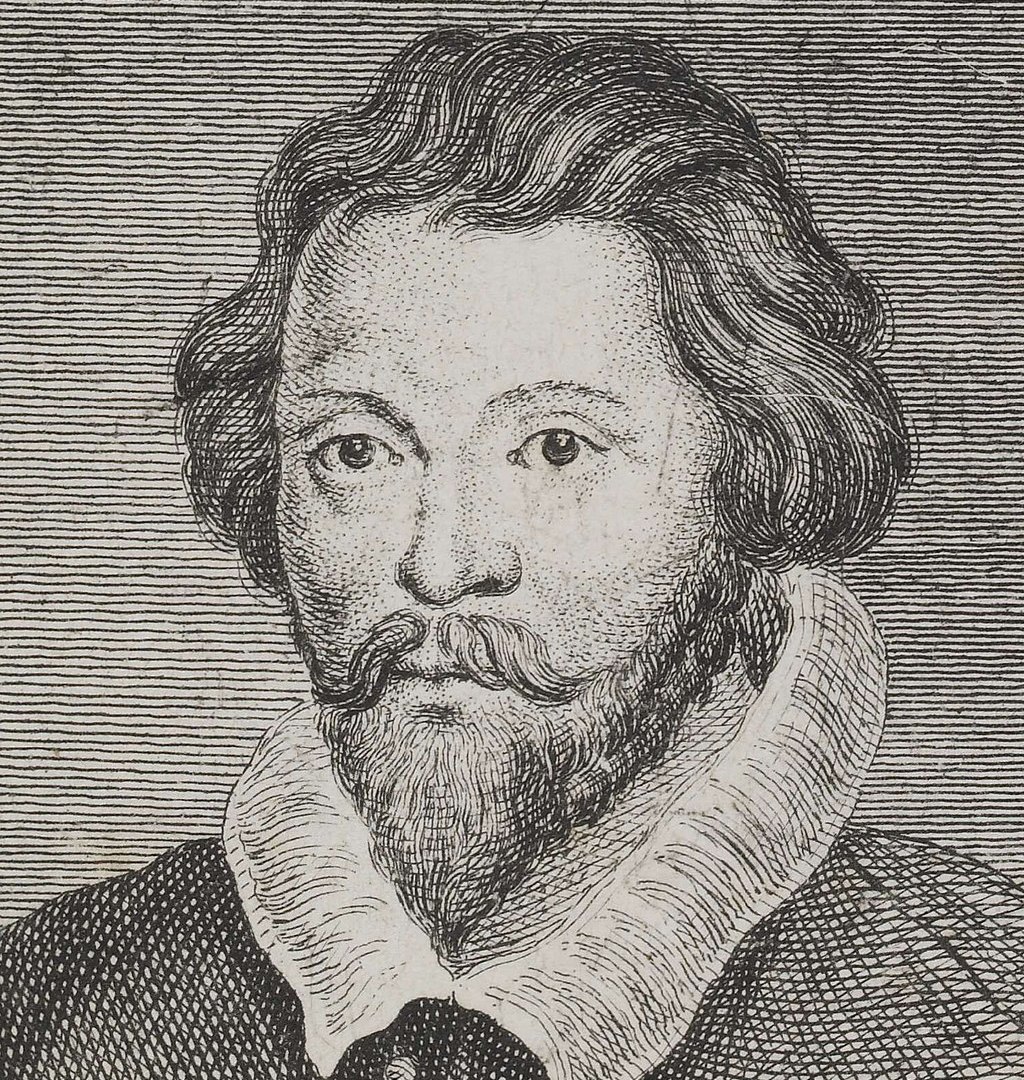

William Byrd 400 years on: celebrating the father of music

Posted on 15th June 2023 at 11:14

It’s been 400 years since his death on 4 July 1623, but the composer William Byrd’s music is still a staple of religious services today. With an enormous output that ranged from simple choral pieces to complex exhibitions of polyphony, Byrd’s music was intrinsically linked to his own Catholic faith and to the Protestant religion that dominated during his life. We look at the impact of his work for his peers, and at the legacy he left for music lovers today.

Byrd was composing during the Renaissance era, a period that saw a huge increase in the number and types of musical instrument available. He produced a wide range of compositions, from psalms and sonnets to music for keyboard instruments such as the harpsichord, and consort pieces designed for ensembles of musicians. And of course, it’s impossible to talk about Byrd’s music without talking about the religious context to his work – both his own Catholic beliefs, and the Protestant faith that prevailed in England at the time he was writing.

Byrd’s early years

Few records survive of Byrd’s early life, but he is believed to have been born in London in around 1540 – just after King Henry VIII had broken with the Catholic church in Rome, and at the start of the Protestant Reformation. Byrd would have been a young adult when Parliament passed the Act of Uniformity, which mandated weekly worship in an Anglican church, using a Common Book of Prayer that was newly translated from Latin to English.

Growing up, it’s thought that he may have been a chorister at St Paul’s Cathedral, or at the prestigious Chapel Royal, where he was certainly a pupil of the renowned composer Thomas Tallis.

From simple pieces to complex compositions

Upon completing his studies, Byrd found employment at Lincoln Cathedral as organist and master of choristers. Examples of the works he composed during his time at Lincoln show a degree of restraint compared to some of his later pieces – with compositions such as In exitru Israel and his Short Service displaying an unpretentious, simple style in line with the demands of the time.

Even in these early days, it seems Byrd’s work was affected by religious tensions, with records suggesting that his salary was withheld on occasion – possibly as a sanction for composing pieces that were viewed as too elaborate and highly-wrought for Protestant tastes. An example of this may have been his free-form Fantasia in A minor, in which, from a simple start, Byrd unleashed his imagination to take the listener on an inventive, increasingly complex journey full of surprises.

Byrd composed for a variety of instruments and settings throughout his career. His writing included consort pieces such as In Nomines that displayed his mastery of polyphony – the practice of using two or more lines of complementary melody – through to the development of verse anthems, which alternated between soloists and a full choir to great effect.

He routinely collaborated with other musicians and composers, such as John Sheppard and William Mundy, and in his use of poems as texts for his songs, helped bring some of the poetry of the day to a wider audience. Poems such as Edward de Vere’s If Women Could Be Fair and Never Fond, Sir Edward Dyer’s My Mind to Me a Kingdom Is and Sir Philip Sidney’s O You That Hear This Voice all found new life thanks to Byrd’s compositions.

Friends in high places

Nearly a decade after taking up the post at Lincoln, Byrd moved to London in 1572 to become a Gentleman of the Chapel Royal – a prestigious title within an establishment that existed to serve the spiritual needs of the royal family. This was a position that opened new doors for Byrd, bringing him into contact with Queen Elizabeth I, who had a keen ear for music and who, despite her Protestant faith, had kept some of the more elaborate rituals associated with Catholicism.

Byrd became a particular favourite of the Queen, and he was granted joint exclusive rights to publish music along with his friend and former teacher, Tallis. The pair collaborated to produce Cantiones sacrae, a series of Latin motets dedicated to the Queen as their first imprint together.

House arrest, and secret music

In 1577, Byrd and his family moved from London to Middlesex, and it appears that his involvement with Catholicism deepened at around the same time. Both he and his wife found themselves in trouble with the authorities for failing to attend Anglican services, and Byrd came under scrutiny due to his association with Thomas Paget, who was later exiled after an unsuccessful plot to overthrow the Protestant queen. Records suggest that at one stage, Byrd was placed under house arrest – although luckily for him, his connection with Elizabeth I led to the charges against him being dropped by order of the Queen.

During this period, Byrd was still producing music for Anglican services, and his Great Service – an enormous, lavish composition that is perhaps his best-known work – was begun in the 1580s. Yet at the same time, he was also composing motets that seemed to express his commitment to Catholicism, drawing on themes of persecution and anxiety.

In 1593 Byrd moved to Essex to be close to his patron, the prominent Catholic Sir John Petre. Among his output in his later years were compositions that were specifically designed for Catholic masses, as well as his Gradualia, a collection of pieces written to accompany services across a full calendar year of the Catholic church. Examining these pieces, often written for a small number of voices compared to the 10-part Great Service, scholars believe these were most likely intended for use by amateur singers at secret Mass celebrations, such as those held at Petre’s home.

Through these works, we can clearly see that Byrd was a man who would not abandon his beliefs, in spite of the dangers for Catholics in England at this time. But his abilities were such that he was highly respected, not just by his Queen but by other composers and musicians of his day.

He was also someone who passed on his knowledge to others – something we at the Music Workshop Company celebrate – and as a teacher he had a huge influence on his students, who included the composers Thomas Morley, Peter Philips and Thomas Tomkins. So it’s perhaps no surprise that upon his death in 1623, he was noted in official records at the Chapel Royal as the ‘father of music’– a title that is still well-deserved today.

Further reading

• Lincoln Cathedral, Byrd’s first employer, is celebrating its connection with the composer as it gears up for the Byrd 400 Festival: https://lincolncathedral.com/byrd-400-celebrating-our-great-choral-composer/

• Rory McCleery, Director of the Marian Consort, explores Byrd’s clandestine Catholic music in this piece for the Guardian: https://www.theguardian.com/music/2020/apr/28/singing-in-secret-william-byrd-isolation

• This blog from the British Library examines the texts of Byrd’s three Masses and his two volumes of Gradualia: https://blogs.bl.uk/music/2018/10/william-byrd-catholic-composer.html

• The BBC’s Classical Music magazine offers its guide to Byrd here: https://www.classical-music.com/composers/william-byrd/

Share this post: