Fanny Mendelssohn Piano Trio Op. 11

Posted on 14th November 2023 at 09:24

Fanny Mendelssohn’s music is now reaching a wider public, having been overshadowed by her more famous brother, Felix Mendelssohn both during her lifetime and in subsequent years. Despite periods of her life where she was unable to compose, Mendelssohn established herself as a composer, conductor and performer in a largely male-dominated environment. Her life highlights some of the challenges female composers have faced throughout history.

We explore her Piano Trio in D minor, Opus 11, which is suggested in the Model Music Curriculum as a piece suitable for Year 5, and offer some activities to help you study the composition.

"Fanny-mendelssohn-9ba7472d-18ca-43cc-9f62-85362217db2-resize-750" by Wikiludiki is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0. To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/?ref=openverse.

Mendelssohn's Life

Mendelssohn was born on 14 November 1805 in Hamburg. She was the eldest child of Abraham and Lea Mendelssohn, with younger siblings, Felix, Rebecka and Paul. The Mendelssohn’s were a Jewish family, but Abraham had concerns about the rise of anti-Semitism in Germany at this time and converted the family to Lutherism, changing the family name to Mendelssohn-Bartholdy.

Mendelssohn’s early talent was supported by her parents, but her status as a woman in the 19th century was impacted by societal expectations. When discussing her musical future compared to her brother’s, her father, wrote to her that: “Music will perhaps become his profession, whilst for you it can and must only be an ornament, and never the root of your being and doing.” Despite this, he acknowledged that Mendelssohn might, had she been male, “have merited equal approval” with her brother. Part of the challenge for Abraham, was his role in society: as a successful banker, he could not have his daughter earning a living as a musician. It has been suggested that if Mendelssohn had grown up in a poor family, she might have had more opportunities for a musical career.

Despite the role of private musician for Fanny and public musician for Felix, the siblings were very close with a mutual appreciation of each other’s’ work, holding one another in high esteem. Their closeness led to them using themes from each other’s work.

In 1825, the family moved to a large mansion in Berlin, which became a hub for scientists and artists, and where Mendelssohn lived even after her marriage.

In 1828, Mendelssohn was engaged to artist Wilhelm Hensel, and considered giving up music entirely on the basis that it was felt to be only for girls, not married women. However, Hensel insisted she continue with her music. They married in 1829.

After the birth of her son, Sebastian Ludwig Felix (named after Bach, Beethoven and her brother), Mendelssohn found it difficult to compose; however, she wrote a piece for her parents’ anniversary followed by her Cholera Cantata in 1831. In September 1832, Mendelssohn had a stillbirth, which again impacted her ability to compose.

It has been suggested that Mendelssohn’s domestic situation was key to her ability to continue to write and perform, within the accepted norms of the day. She hosted “Sonntagsmusiken” – Sunday musical events. These concerts were an important part of Berlin’s musical life, and visiting musicians such as Liszt sought invitations to perform. One of the benefits was that Mendelssohn insisted on silence from the audience – a novelty at the time.

Image: Yair Haklai, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

The composer Johanna Kinkel commented:

“When one saw Fanny Hensel perform a masterpiece, she seemed larger. Her forehead shone, her features were ennobled, and one believed in seeing the most lovely shapes … No common feeling could have possessed her, she must have been contemplating and breathing in the realm of the sublime and beautiful.”

To publish or not to publish

One point on which Fanny and Felix did not agree was whether Fanny should publish her compositions. Fanny Mendelssohn, supported by her husband and mother, wanted to publish her works, but Felix was against this. He wrote to his mother saying that he would support her:

“But to encourage her to publish I cannot do, since it runs counter to my views and convictions … I regard publishing as something serious (it should at least be that) and believe one should do it only if one is willing to appear and remain an author for one’s life. That means a series of works, one after the other, to come forward with just one or two is only to annoy the public.”

Felix went on to say that in his opinion, his sister would not want to be under the pressure to continually publish as her focus was on her home and her son. However, he requested that his mother should not show the letter to his sister or her husband. Felix then restated that he would support her, but would not encourage her.

Mendelssohn continued to push the line between public and private music, and in 1943 she wrote a piano sonata, a musical form that was seen largely as a male area of expertise.

In April 1846, Mendelssohn met diplomat and music-lover Robert van Keudall who encouraged her to compile a collection of her compositions, both old and new. In June that year, she wrote to her brother:

“... since I know right from the start that you won’t approve, it’s a bit awkward to get underway….. In a word, I’m beginning to publish. I have Herr Bock’s sincere offer for my lieder and have finally turned a receptive ear to his favourable terms. And I’ve done it of my own free will and cannot blame anyone in my family if aggravation results from it…If it succeeds – that is, if the pieces are well liked and I receive additional offers – I know it will be a great stimulus to me, something I’ve always needed in order to create. If not, I’ll be as indifferent as I’ve always been and not be upset, and then if I work less, or stop completely, nothing will have been lost by that either.”

It took four weeks for Felix to respond, offering his “professional blessing on your decision to join our guild”, stating “may the public pelt you only with roses and never with sand.” Mendelssohn noted:

“At last Felix has written, and given me his professional blessing in his kindest manner. I know that he is not quite satisfied in his heart of hearts, but I am glad he has said a kind word to me about it.”

1846 then became a prolific time of writing for Mendelssohn, where she committed to regular composing as well as revising and developing works. One of the new works of this period was the Piano Trio in D minor Opus 11. However, as political tensions increased around her, Mendelssohn struggled to compose more, writing that “nothing musical is succeeding for me – since my trio I have not written a useable bar.”

Mendelssohn continued organising Sunday concerts and on Saturday 14th May in rehearsal with the chorus, she lost sensation in her hands. This had been a long term issue for her, but as she left the rehearsal to treat her hands, she collapsed with a stroke, dying later that night.

Context for Mendelssohn's Musical Life

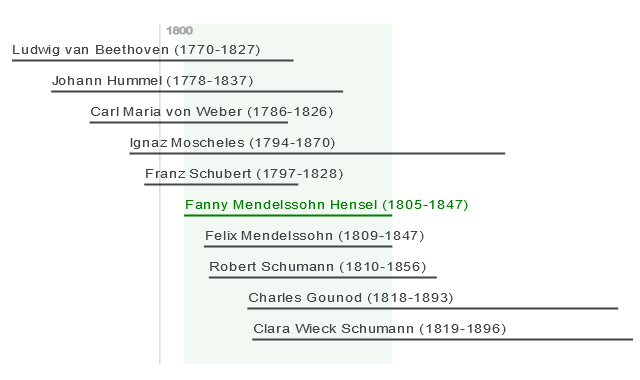

It is helpful to place Mendelssohn in the context of her fellow composers.

Taken from https://www.earsense.org/chamber-music/Fanny-Mendelssohn-Hensel-Piano-Trio-in-d-minor-Op-11/

Moscheles was one of her teachers, and she was a great inspiration to both Gounod and Wieck Schumann.

Piano Trio in D minor Opus 11

The piece began at the end of 1846 as a birthday present for Mendelssohn’s sister, Rebecka. Mendelssohn premiered the piece at one of her celebrated Sunday Salon’s, on 11 April 1847, with Robert von Keudell playing the violin, and her brother Paul on the cello.

It is written in four movements, as is usual for Piano Trios. They are labelled :

1. Allegro molto vivace

2. Andante espressivo

3. Lied: Allegretto

4. Allegretto moderato

The score can be found here.

The first movement of the Piano Trio is marked “allegro molto vivace” meaning the piece should be played quickly and in a lively manner.

The movement opens strongly, bursting with energy despite being played quietly. There are moments of lyricism, highlighting Mendelssohn’s skill in writing Lieder (songs). Mendelssohn’s performance skills as a pianist are showcased, as the piano part is technically very demanding.

Instrumentation

The instrumentation is the usual group of instruments for a piano trio:

Violin

Cello

Piano

Activities

As this piece is written for just 3 instruments, it is a good piece to develop score reading skills. On the score, the violin part is the top line, the cello is the next line and the bottom 2 lines of the score are the piano part.

When following the score, you can pick one line of music to follow, or you can follow the main melodies as they move between the instruments.

This video allows you to follow the score while you listen to the music:

Some things to notice:

When do all three instruments play together?

When the instruments play together, are they playing the same rhythms as each other?

Are they playing fast notes or slow notes?

Are there any places where the violin or the cello play alone?

Can you hear or see on the score, when violin and cello are playing Pizzicato – plucking the strings, marked “pizz” on the score?

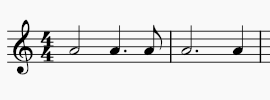

How many times is this rhythm used?

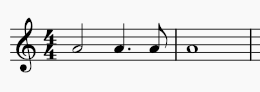

How many times is this rhythm used?

What's the highest number of notes played together at any one time?

References include:

Anna Beer – Sounds and Sweet Airs – The Forgotten Women of Classical Music - https://oneworld-publications.com/work/sounds-and-sweet-airs/

Share this post: