Sol-Fa – Singing Through the Ages

Posted on 14th November 2016 at 14:00

November 14th 2016 marks the 200th anniversary of the birth of John Curwen, an English Congregational Minister and music educator who was responsible for refining and popularising the tonic sol-fa system of musical notation. Although he did not invent tonic sol-fa, Curwen developed a distinct method of applying it in music education which included important aspects of both rhythm and pitch that have been formative in much of the singing and early-years music teaching ever since.

The sol-fa, or solfège, system is designed for singing. If you have ever heard the song Do Re Mi from Rogers and Hammerstein’s musical The Sound of Music, you will be familiar with the idea. This concept transfers over to instrumental learning with the understanding that children can learn a great deal about pitch, rhythm and tone by learning to sing which can then be applied on any instrument.

Initially developed in the form we recognise today by Sarah Glover (1785-1867) a music teacher from Norwich, to aid Sunday School teachers with a cappella singing, Glover’s teaching method used movable solmisation syllables (a system of attributing a distinct syllable to each note in a musical scale) as an aid to sight-reading, alongside a sol-fa notation, which she had devised as a stepping stone to reading music from the staff.

There is evidence to suggest that a similar system of solmisation existed many centuries earlier. In her research paper Non-Lexical Vocables in Scottish Music, Christine Knox Chambers of Edinburgh University traces the use of solmisation back to China, Korea and even the Native American tribes. In Indian Classical Music the notes of the basic seven-note scale have the names sa, re, ma, ga, pa, dha and ni. And in Scottish Gaelic, the word canntaireachd (chanting) refers to an ancient Scottish Highland method of solemnisation which ‘notated’ music played on the Great Highland Bagpipes. This made it possible for music to be passed on in the aural tradition even without instruments.

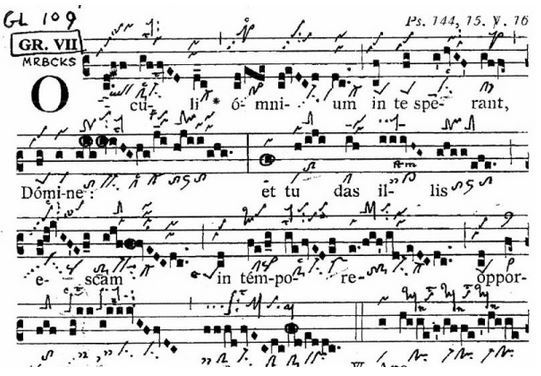

Sol-fa or solfège as we know it was first seen in Europe in the 11th century, developed by Guido d’Arezzo, a music theorist and a monk of the Benedictine order who is credited with inventing modern staff notation. Staff notation replaced a system called neumatic notation, an ancient system of inflective marks which indicated the general shape of the musical line but not necessarily the exact notes or rhythms to be sung.

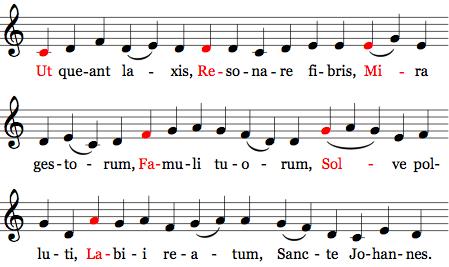

Arezzo’s original solfège note names derive from an 11th-century hymn in which the solfège syllable is the word accompanying the first note of each phrase. The starting notes of each phrase are C, D, E, F, G, A:

[image source https://blog.key-notes.com/solfege.html%5D

In the sol-fa method, the seven tones of the scale are named do, ray, me, fah, soh, lah and te and are arranged into ascending and descending scales where do is the note C.

There is also a method called moveable do, which Curwen and Glover both employed, where the note do can be the tonic in any key.

Having experienced considerable difficulty himself with music reading and traditional music notation, Curwen became interested in the sol-fa method and its potential for teaching and developing music reading. He felt the need for a simple way of teaching how to sing. He believed that music should be easily accessible to all classes and ages of people.

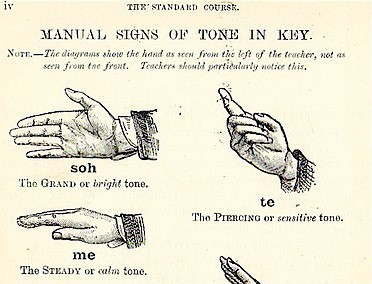

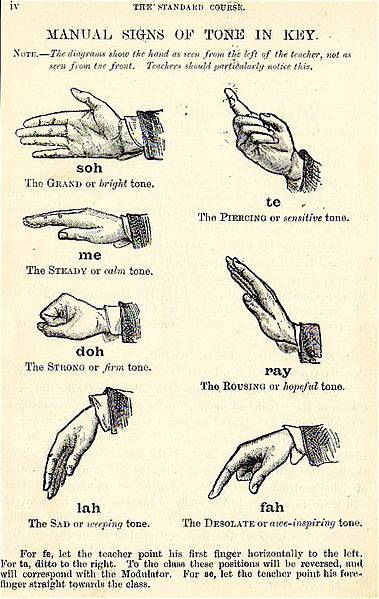

In order to facilitate this, he devised a step-by step approach to teaching: Firstly reading from sol-fa notation, secondly reading from staff notation in conjunction with sol-fa notation below, and thirdly reading from staff notation alone. As his ideas developed he devised the pitch hand signs that are familiar to most music teachers as part of the Kodály Method and incorporated the French time names which are familiar from childhood music lessons (taa taa, titi). The use of sol-fa served as a memory aid as well as a learning aid.

Many of his pedagogical ideas are fundamental not only to other music teaching methods such as Kodály and Dalcroze, but also to general educational practice.

Curwen’s principles of education:

Let the easy come before the difficult

Introduce the real and concrete before the ideal or abstract

Do one thing at a time

Let each step, as far as possible, rise out of that which goes before, and lead up to that which comes after

Call in the understanding to assist the skill at every stage

Share this post: